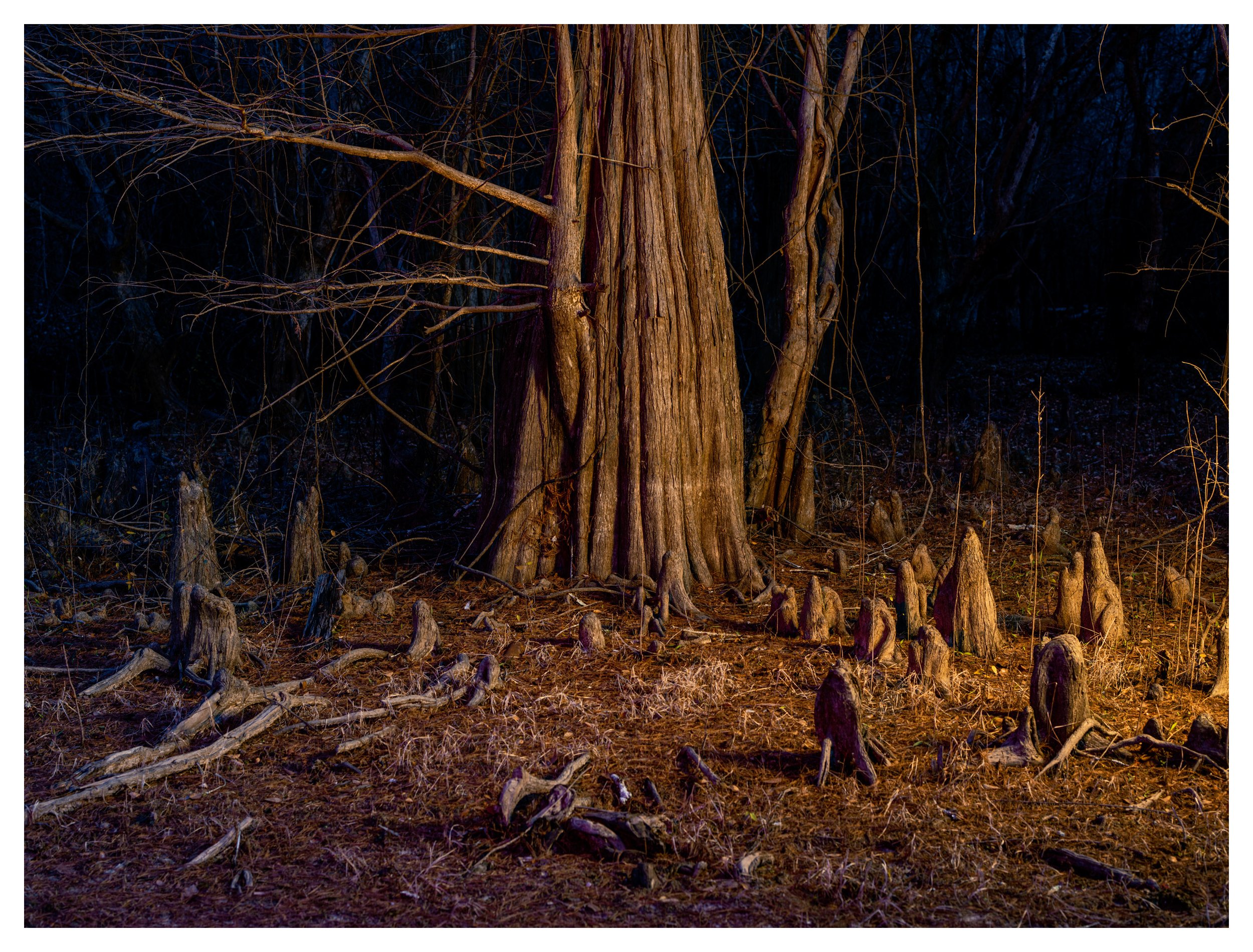

For two years my partner and I lived above the BTC Old Fashioned Grocery in a small town called Water Valley in Mississippi’s hill country. The town was built around a railroad depot financed by wealthy cotton planters just before the Civil War and it is still home to three thousand people. We spent our mornings eavesdropping through the floorboards listening to the characters chatting below, imagining ways to make photographs of this place. Eventually, this town and its surrounds set the stage for the photographs in Knit Club, although the images were not made until years after I had left.

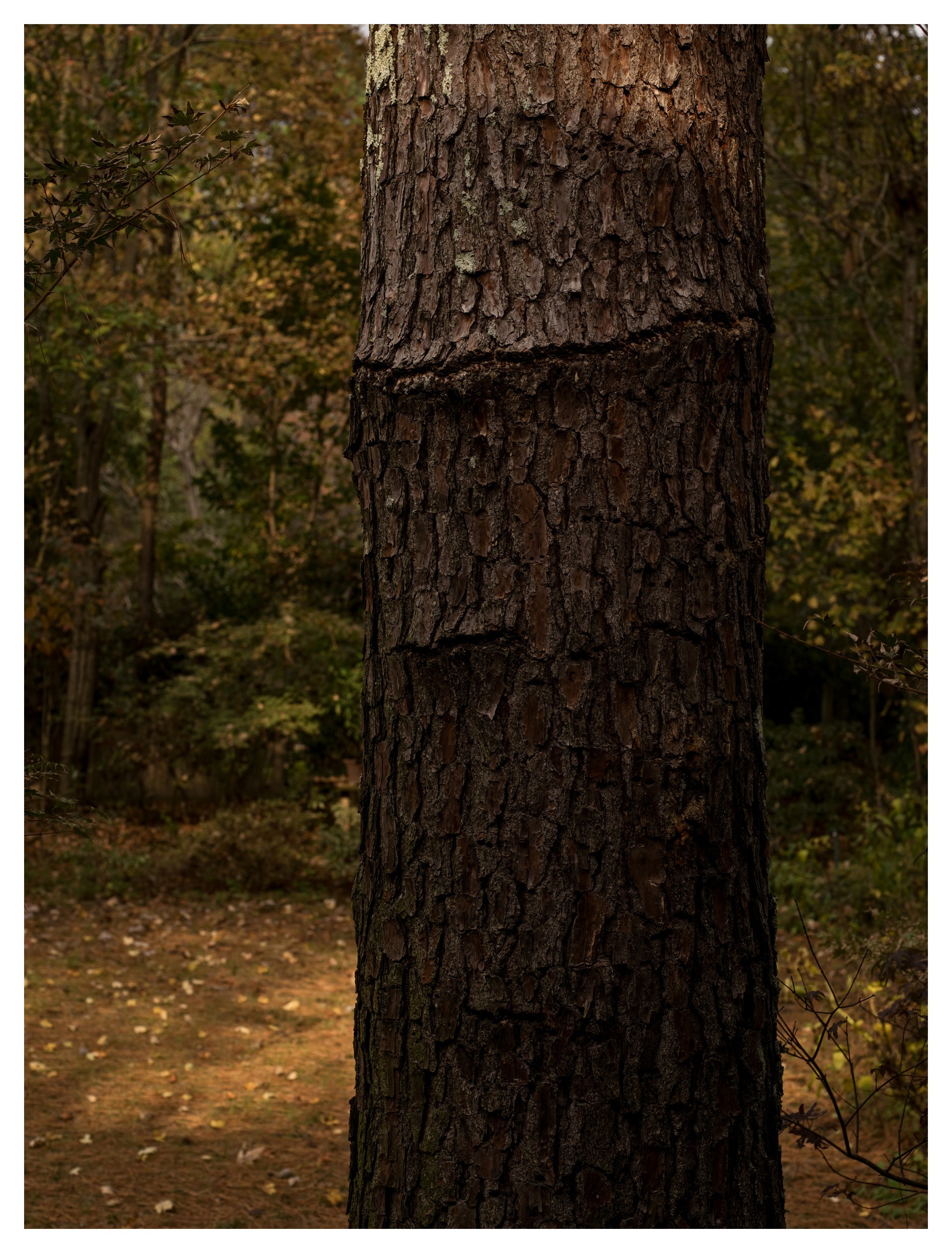

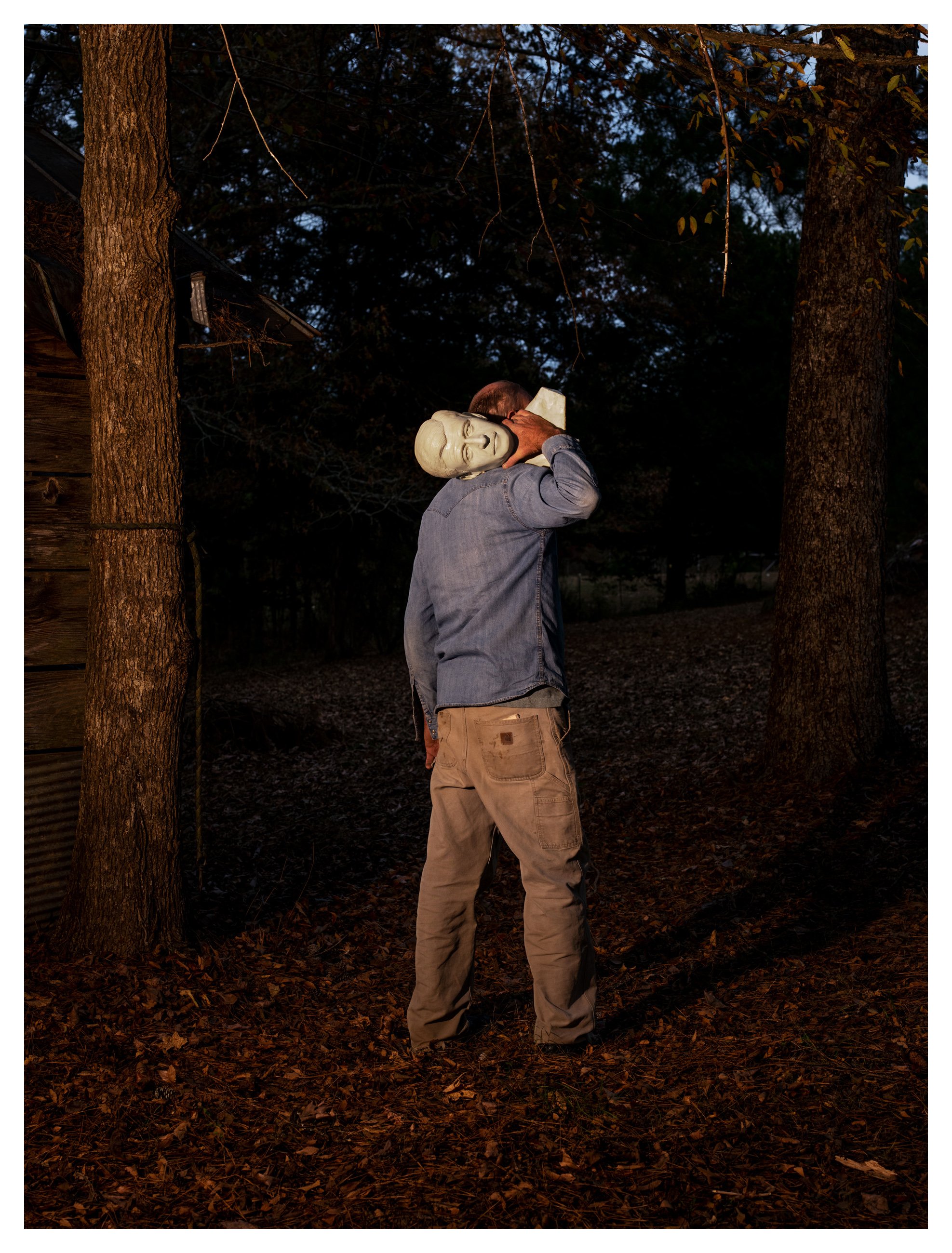

Being present in Water Valley on a daily basis made me feel I knew a lot of things: that the First Baptist Church was the seat of political power; that it was impossible, given the politics in the town, for a black business owner to survive on Main Street; that beer, not liquor, was illegal there until 2007; that what I read in the newspaper was not always true. But this didn’t explain why my neighbor slept with a gun under her pillow or why the furniture maker started installing concrete devils around town.

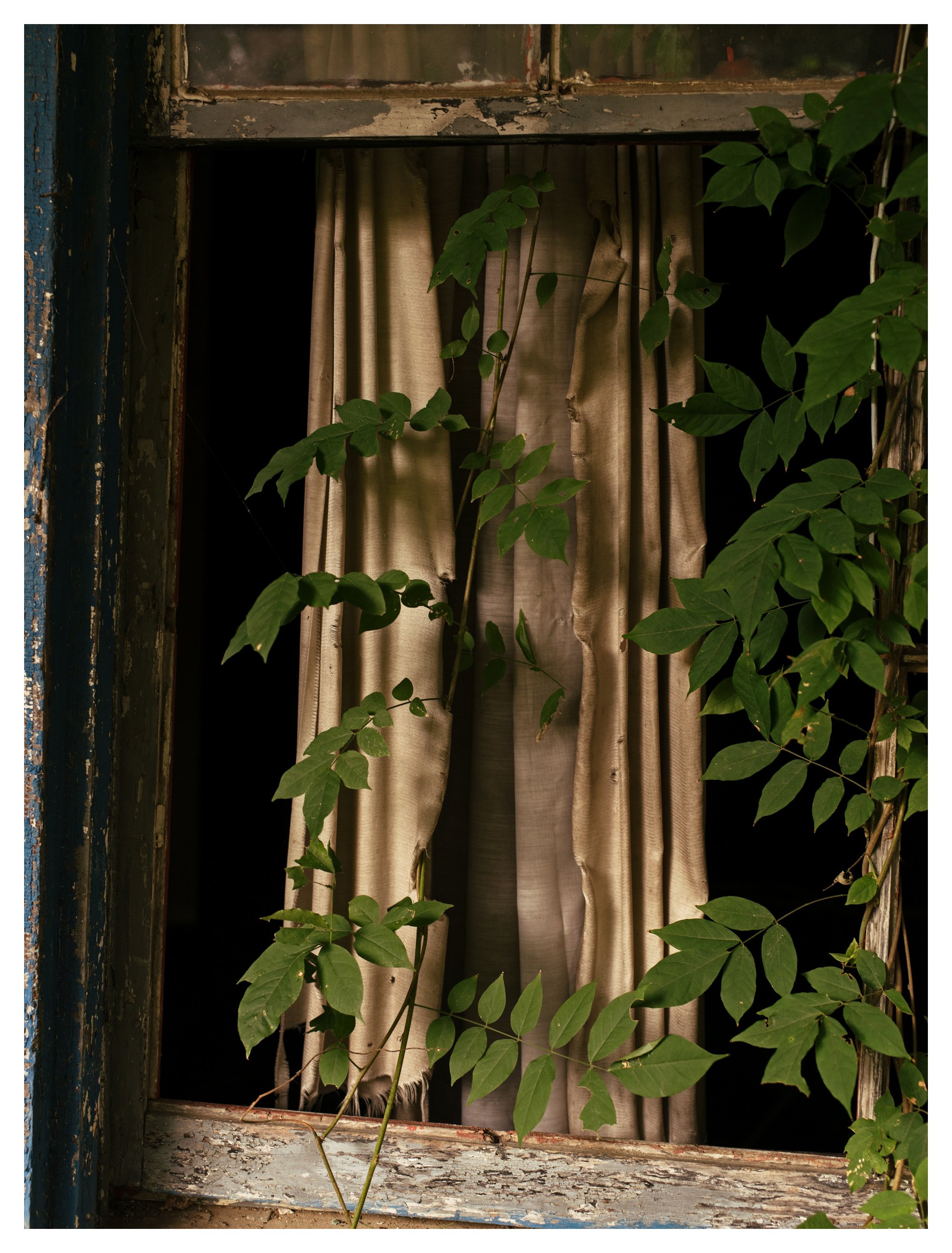

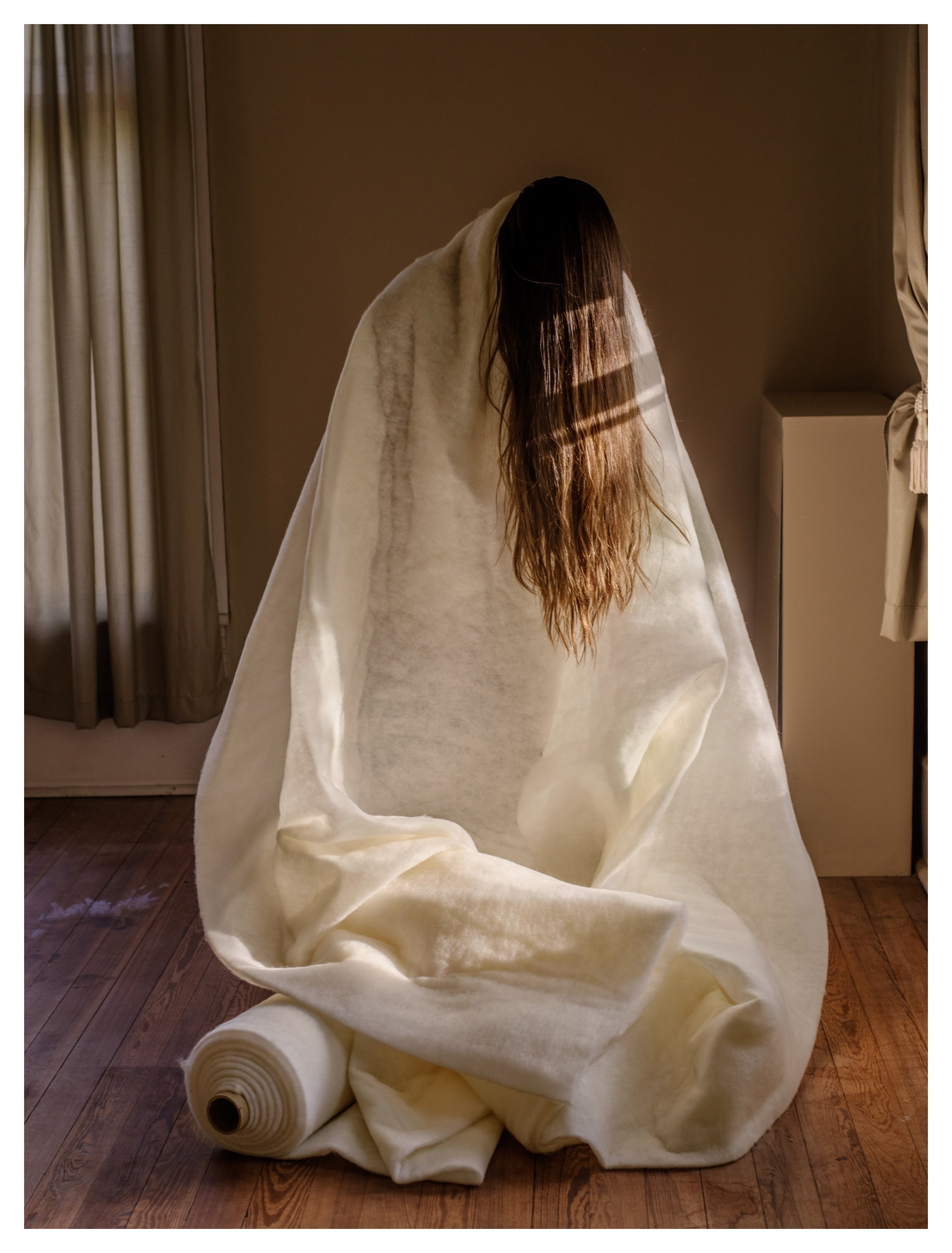

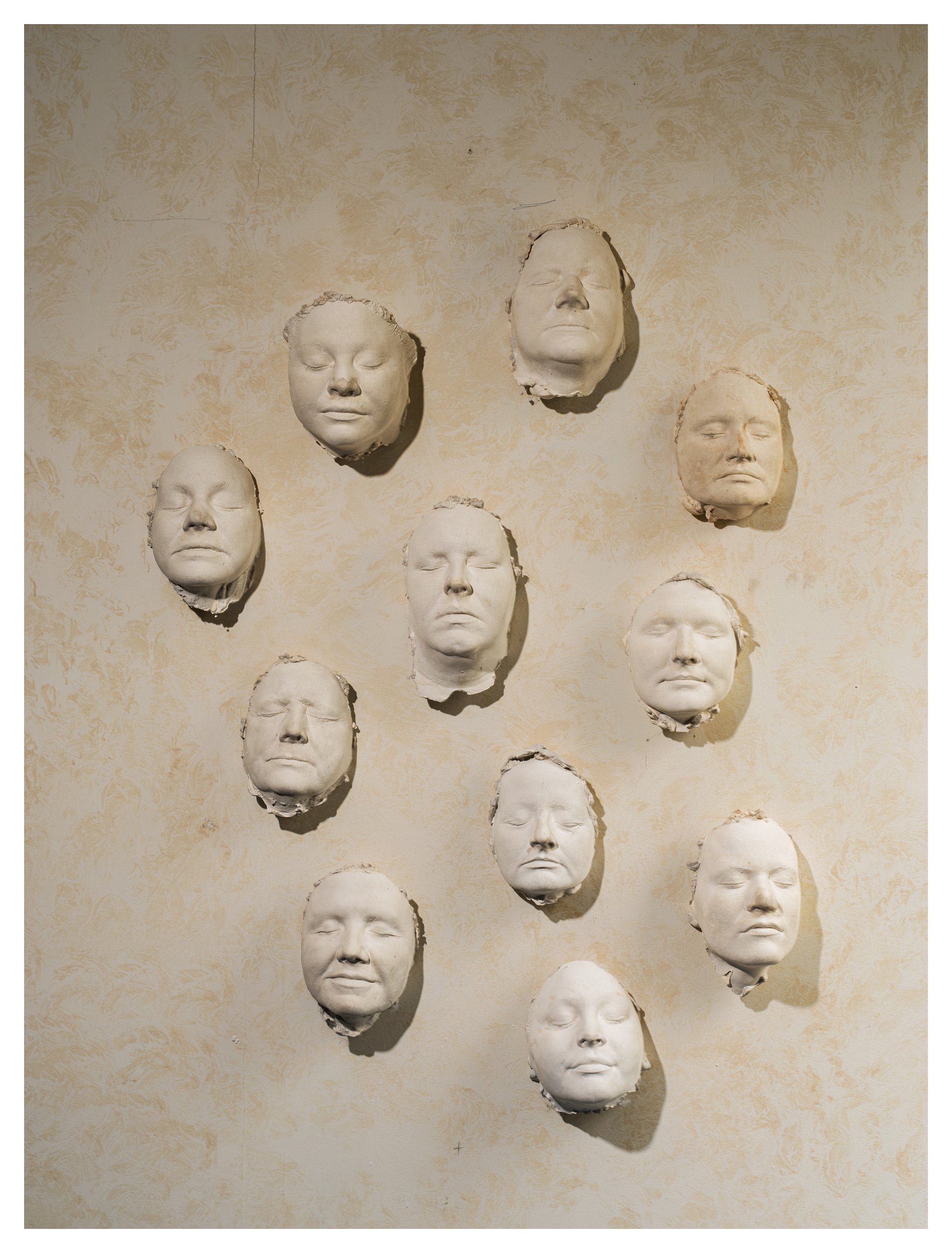

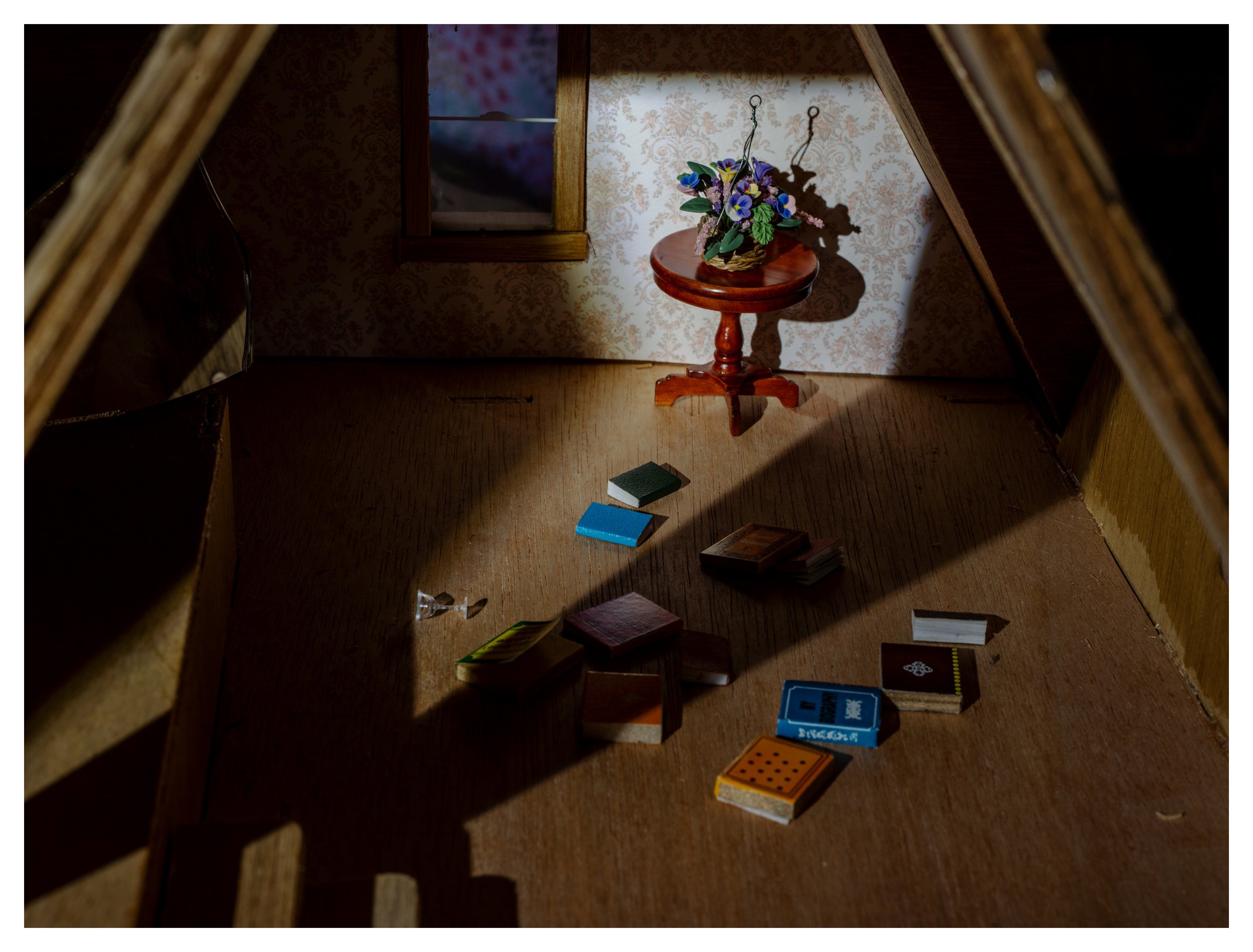

Eventually we moved away, but I continued to return to Water Valley again and again without my partner, looking for connection. It wasn’t until I finally put the camera down, let down my guard, and joined the conversations instead of sitting on the outside listening through the floorboards, that the ideas in Knit Club started to take shape. A friend invited me to sit on the porch with a group of women whose lives were entangled in a knitting circle, and I slowly learned to sew, quilt, and drink prosecco after dark with children whirling around us. I listened to stories about the divorce proceedings of the textile artist, the waitress training to be a teacher, the housewife cleaning out her attic while her husband worked on the railroad, and I shared stories about my own financial struggles and my traumatic ride-along with the police deputy and my move to California.

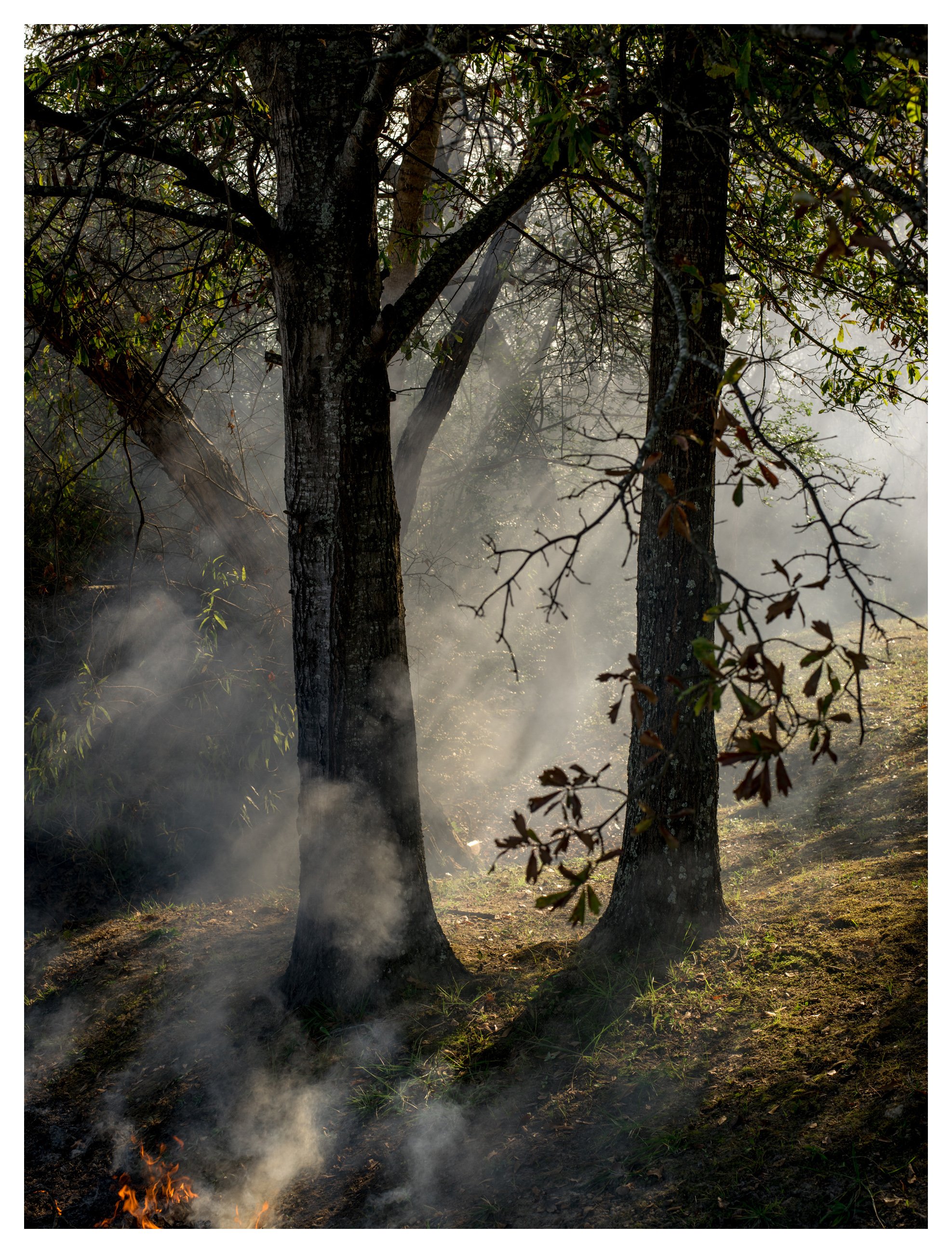

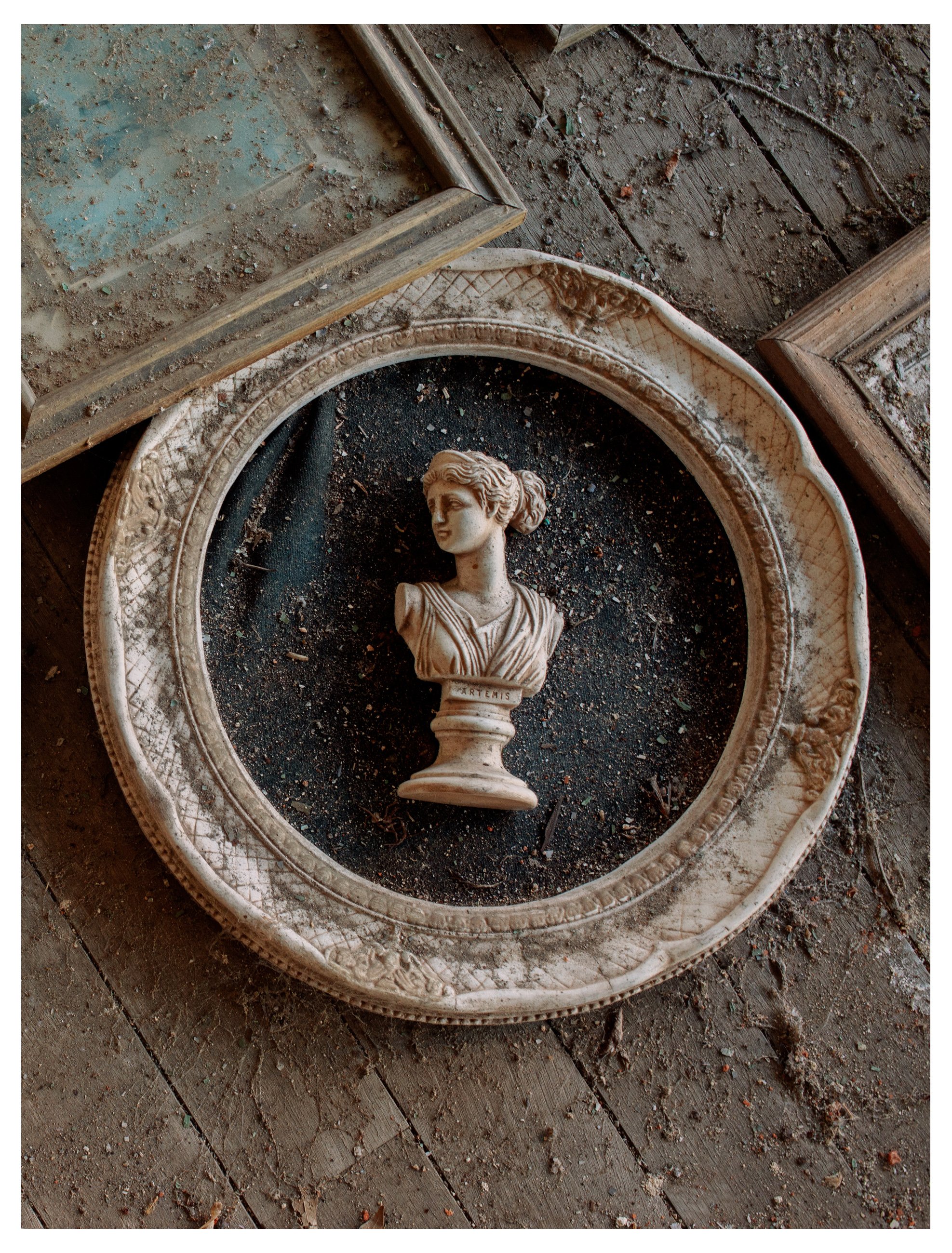

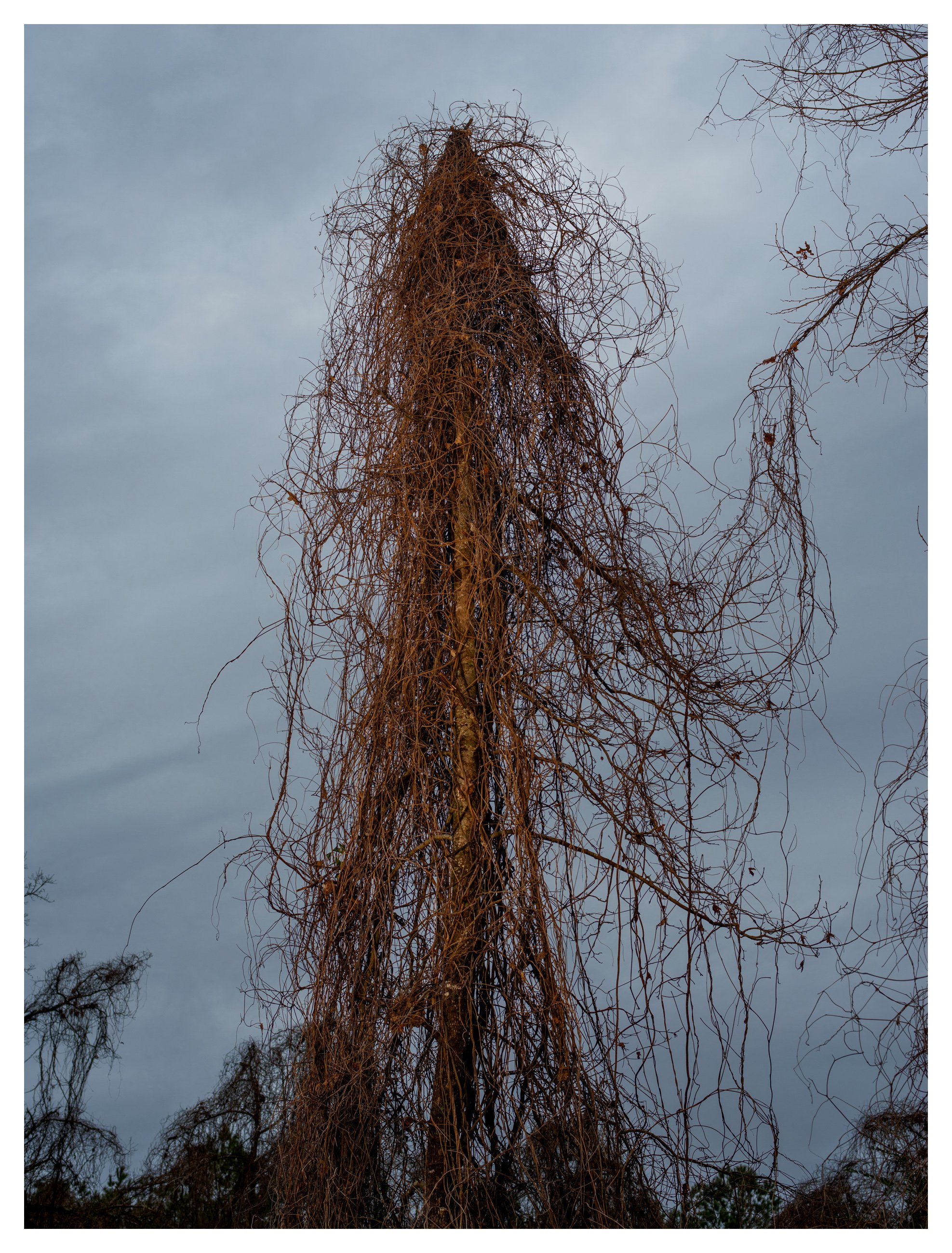

The county adjacent to Water Valley was the source of much of William Faulkner’s fiction, and I began to read his novels for the first time during this period. His characters, speaking in rambling sentences that run across paragraphs, are driven by forces that are a mystery not only to the reader but to themselves. You don’t know them well or understand them, but you feel them. I was haunted by the way that family members of the matriarch Addie Bundren in As I Lay Dying jostled to please their own subconscious desires while traveling in a broken wagon to lay her body to rest. These old stories rooted in this place opened a door for my imagination.

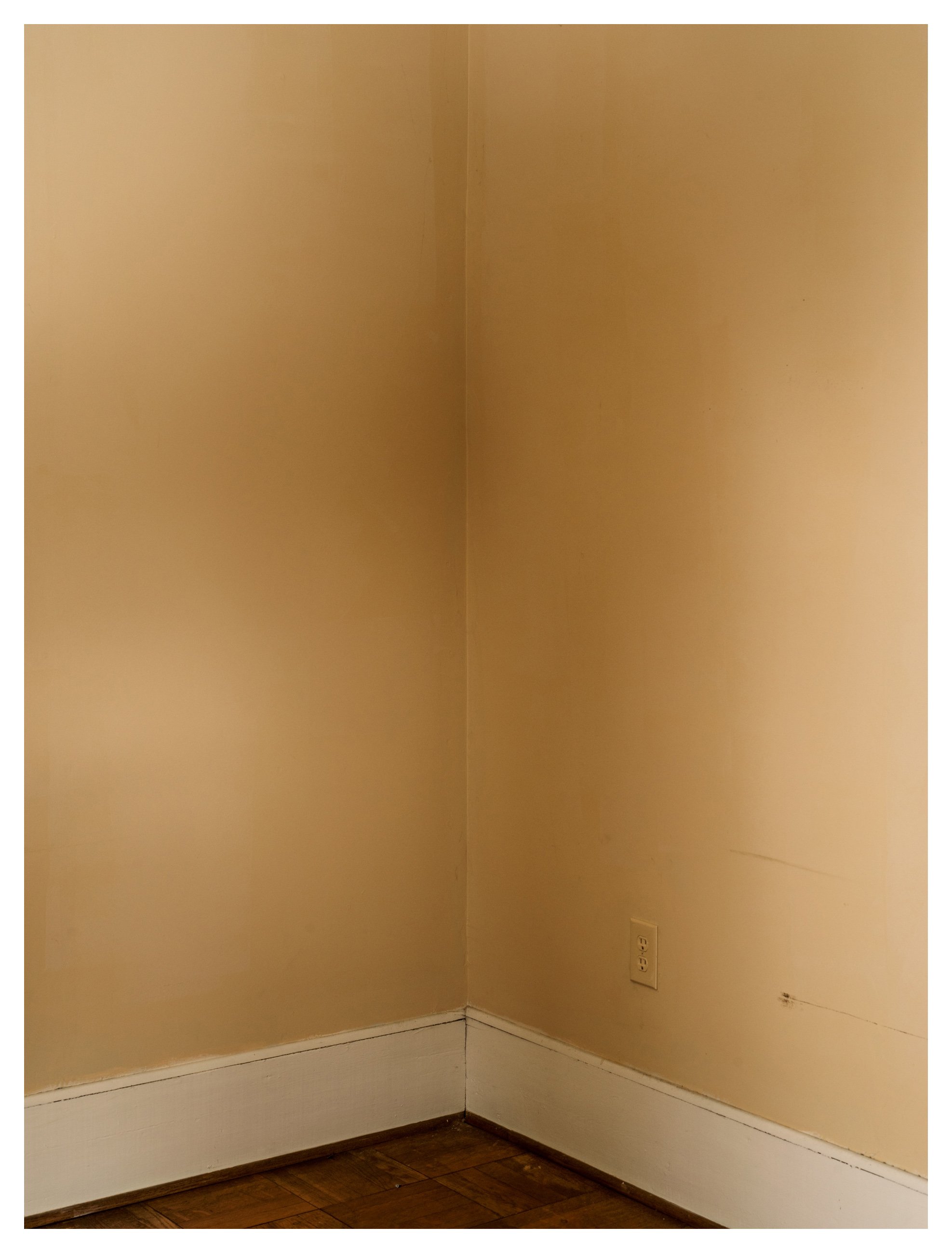

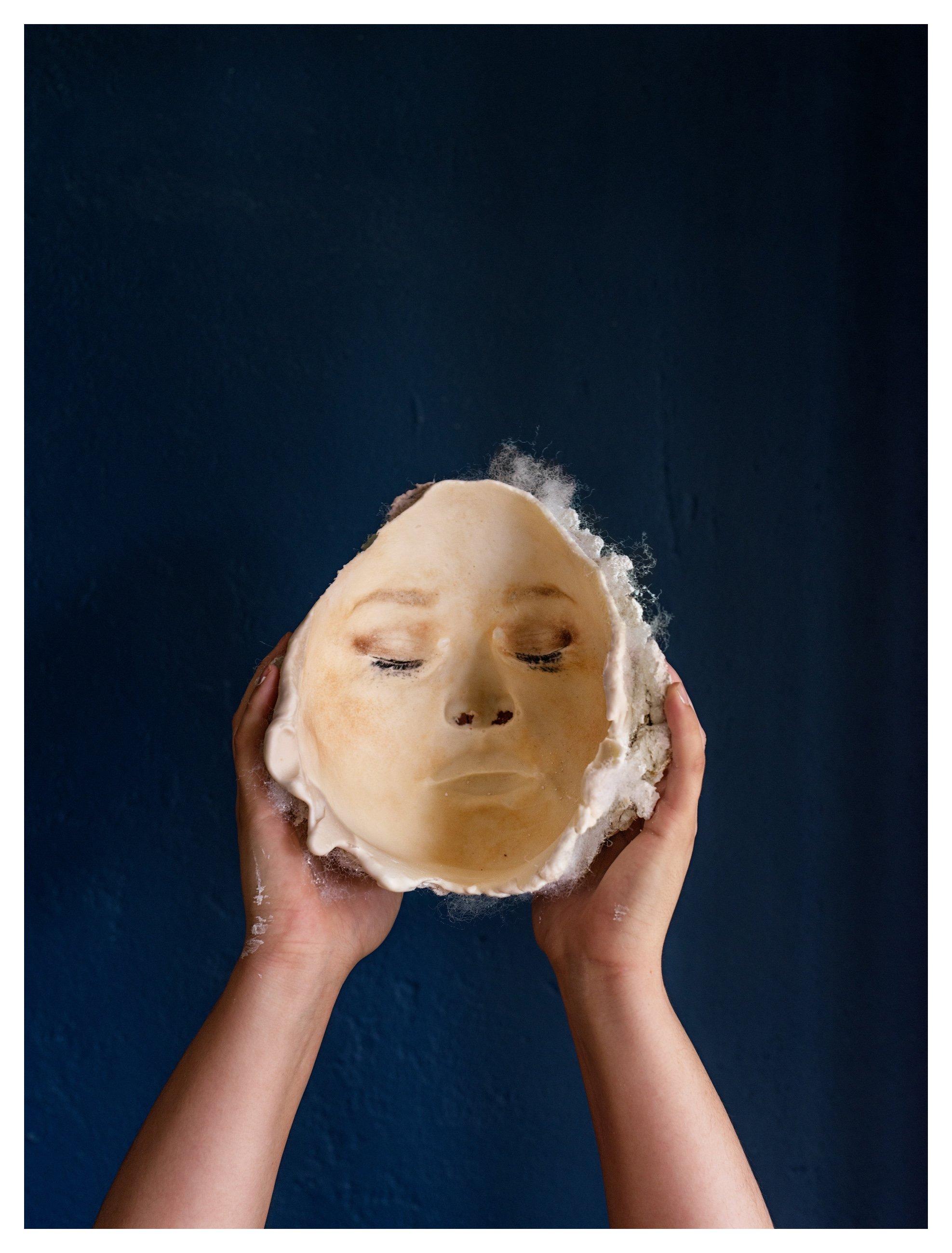

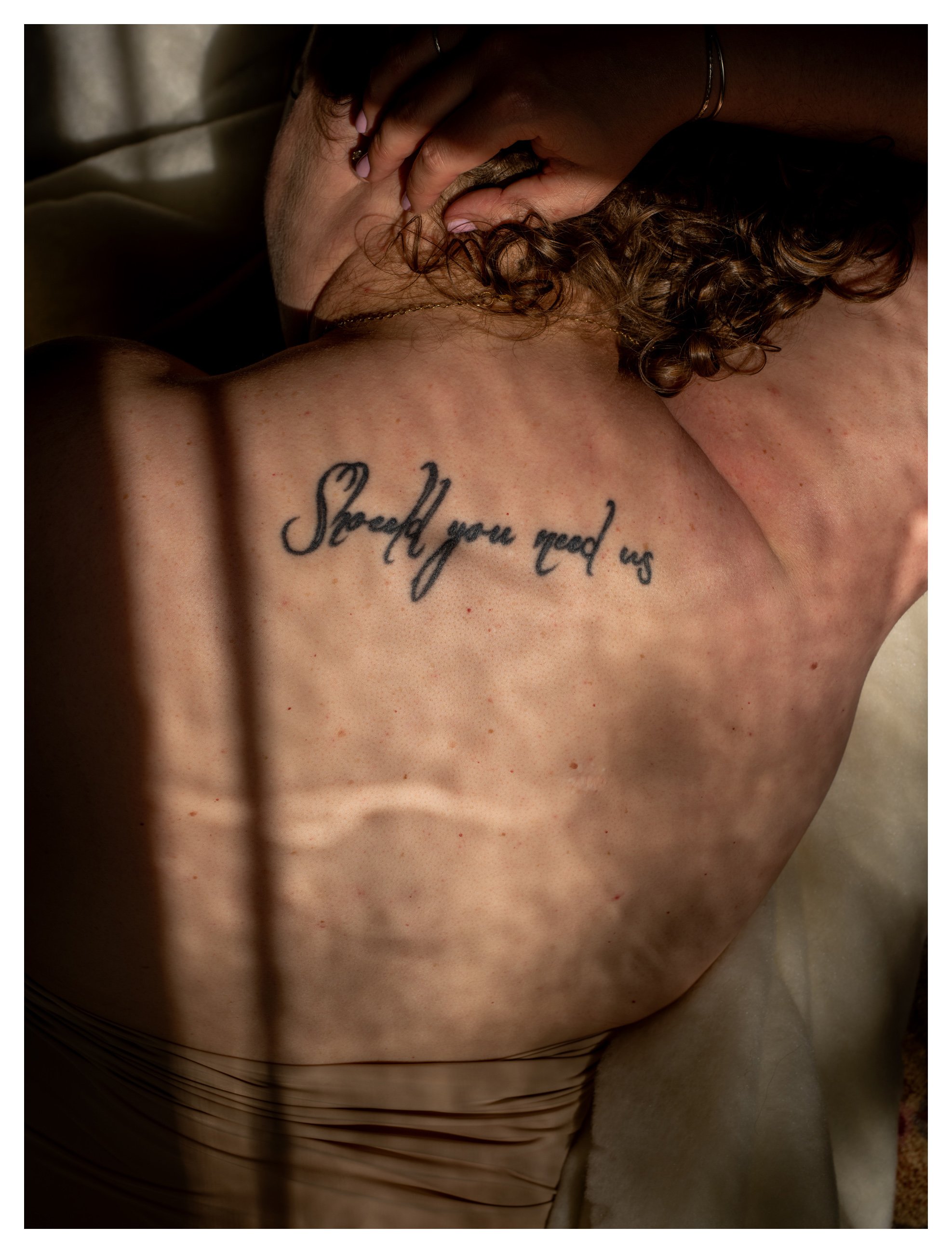

In time, I invited the women in the sewing circle to be in my photographs. But the women of Knit Club embody a different kind of character than Faulkner’s women. Not the dead Addie Bundren, but living people with agency and secrets, acting behind the scenes, untamed, often without being seen. We worked alongside each other, trading places, telling stories, collecting material. Subconsciously, then consciously, making this work was a way to explore my own conflicted relationship with womanhood. Why had I arranged my life to avoid feeling trapped in domesticity, and why was I suddenly attracted to some parts of it? At what point had I chosen not to have children of my own? We worked instinctively with what we had, part them, part me, all us, fulfilling a desire and a need that had roots and branches but will never be tied in a bow.